Neil Mendoza (United Kingdom, 1977) is one of the world’s biggest names of new media, where experimental art meets technology and electronics, and one of the main guests of Offf Sevilla 2022. Although he modestly defines himself as «maker of stuff», his talent as a programmer has led him to apply his mathematical and computer training to bold, playful and surprising installations. A teacher at institutions as serious as UCLA and Stanford, his creative work ironizes on the most absurd and banal aspects of contemporary life, looking with strangeness at the objetcs to which he breathes life and which he has exhibited at the Ars Electronica Center, the Barbican or the Arena 1 Gallery, among other prestigious places.

How do you think your scientific way of thinking contributes to your artistic work and how is it reflected in it?

Elements of my process definitely have parallels with the scientific method, proposing hypotheses and then running experiments to test them. Sometimes these hypotheses consider aesthetics, sometimes engineering or sometimes just putting different ideas in conversation. The thing that is challenging, but can lead to interesting results, is the tension between the logical engineering side and the creative side of my work. Logical thinking involves reasoning along well trodden neural pathways whereas creativity is about exploring new ideas and ways of thinking.

Your discovery of Processing, a tool for making generative art, must have been somehow like starting to play. Does that playful spirit still guide you when approaching experimental art?

When I studied maths and computer science as an undergrad it was very rigid with no space for creativity. It wasn’t until I saw a colleague at a branding agency experimenting with an early version of Processing that my mind was really opened to the potential of technology as a playground for creativity. Since then, play and experimentation has been an integral part of my process. Being an artist is like being a research scientist in the field of reality, exploring the synergy of ideas, aesthetics and technology. It gives you the freedom to learn about any field and immediately apply that knowledge to your practice.

In 2014 you co-founded the art collective is this good?, which, due to its freedom and lack of pretensions, sounds to me like the opposite of a Silicon Valley startup. Do you think creativity is too conditioned today by productivity?

In contexts such as advertising agencies, creativity is definitely packaged into a well defined step by step process that doesn’t leave much space for experimentation. However, I don’t think that creativity is universally conditioned by productivity. In smaller companies, like is this good? or an indie game developer, there’s no dogma around how a project should be structured so there’s space for play.

The cult of productivity is itself often a performance in absurdity. For instance, college costs in the US have soared over the last few decades and a lot of that money goes to support administrators and administrators administrating other administrators while the number of professors hasn’t increased that much. Jobs like this, that support a company’s growth rather than the need they are supposedly fulfilling, are becoming more commonplace. I am very lucky in that I have the time to create art and feel like in some ways the act of creating these unnecessarily complex absurd machines is a comment on work as a performative act.

You’ve said that, when dealing with art, technology should remain in the background, but also that “it’s easy to get trapped in technical rabbit holes”. Is it something that you have managed to avoid over the years? Are technological innovations less appealing to you these days?

This question brings up a couple of different issues. The first is around using recent technological innovations to create art. Using the newest, shiniest toys is definitely enticing but it’s often difficult to express artistic ideas with these media. They get lost in the novelty of the tech. When Oculus launched the DK1 and rebooted the VR industry that had been dormant since the 90s, people at art shows were getting excited about the experience of VR itself rather than any specific content.

The second relates to the process of creation with technology. Software and mechanical engineering are both crafts and it can be very easy to spend too much time on the “beauty” of the technical aspects of a piece at the expense of the final piece. While it’s good to have software that works reliably, having beautifully structured code (that nobody ever sees) is not going to make your artwork have a more profound effect on anyone. However, I’ve definitely fallen down this rabbit hole a few times.

The motto of this year’s OFFF Sevilla (Made for the curious) poses curiosity in design as a consequence of the prevailing chaos in a world where order is threatened. What sparks your curiosity, creatively speaking?

Moments of curiosity often occur when I give my brain a chance to relax and step away from whatever I’m working on. I might be at a yoga class when suddenly my subconscious will go into high gear and start throwing ideas at me, telling me to pick up my phone and take notes. I think creativity can be fostered by guiding people to ideas that excite them and showing them how they can use new skills to explore those ideas.

Do you think that curiosity can be a characteristic of the artificial intelligence? What aspect interests you the most about the possibilities of robotics?

Artists are already using AI as a tool for curiosity, for instance, exploring the latent space of GANs and using text to image models. These kinds of image creation tools are especially interesting as a way of collaborating with machines, using them as a source of inspiration as part of a larger creative process.

Advances in robotics have already brought us digital fabrication tools that allow individuals to create objects that would have taken a whole team of people and a factory a few decades ago. I’m excited about exploring the possibilities of combining AI with robotics in an artistic context. One recent piece I made used a neural network to generate text that was typed by a team of robotic Spam cans and going forward, I’d like to experiment with machines that teach themselves to interact with each other and the world in unexpected ways.

Your works of art tend, on the one hand, to humanize technologies and, on the other, to show their most disturbing side. Don’t you think that algorithms cause the death of the unpredictable and the unexpected?

I think it’s good to show both sides of the coin. In the media, everything is binary, categorized as black or white when in fact the world is nuanced and shades of gray. Technology has had incredible positive effects, such as the reduction in infant mortality, and obvious negative effects including the creation of numerous unsustainable industries. In the end, it’s up to us to take technology in the direction we would like it to go.

I don’t think algorithms will lead to the death of the unexpected. Each algorithm on its own will react in a deterministic way given a specific set of inputs. However, there are so many of these systems interacting with each other and chaotic data sets that, as a whole, they are as hard to predict as the weather. In addition to that, machine learning systems are becoming ever more prevalent and their inner workings are a lot more opaque than systems that are programmed rather than trained.

The Fragility of Complexity makes me think about the threat that lies in every complex and perfect system, while Mechanical Masterpieces could be understood as a trivialization of art. Do you think contemporary art tends to be too insubstantial?

There’s a broad range of contemporary art from works about pop culture icons through to pieces that are totally inscrutable without a PhD. What rises to the “top” is a function of so many different factors external to the art itself including luck, zeitgeist, money, virality and a million other things. However, some of the most famous artists are as skilled at PR and marketing as they are at the creation of art so that definitely leads to some distortions. I don’t think art needs to be insubstantial to draw people in but if these insubstantial works act as a gateway into the wider appreciation of art then I think that’s a good thing.

You say with irony that Mechanical Masterpieces is “optimized for short attention spans”, how do you think art can compete with the absorbing digital contents?

Social media has allowed for the weaponization of content, promoting media that is going to keep us scrolling, often showing us content that exacerbates negative emotions. In this landscape, art can provide a much needed counterpoint providing works and curation that are driven by ideas and aesthetics rather than likes. Physical art spaces also offer a social element that these single user screen based experiences do not.

Although you use technology, the presence of the mechanical, for which it is necessary to use human force, is also a constant in your work. Why are you interested in this combination or tension?

We’ve evolved to interact and perceive the world in three dimensions and suddenly huge swaths of people are mediating their day to day interactions through screen based abstractions of the world. We lose all the sensory information outside of sight and sound with these devices and even those two aspects are homogenized. I love the possibilities that digital technology presents and when combined with physical elements, it is easier to create a deeper connection with your audience.

Also, as I mentioned in answer to your previous question, creating works that have a spatial element creates a place for people to interact with the works as well as each other.

Everyday objects, if seen out of context, can be weird and even grotesque. It’s that contrast which makes arise the absurd and the humor in your work, isnt’t it?

Taking everyday objects out of context breaks down our subconscious filters around them and lets us see them like a child would. You can then use this new found relationship with the objects as a backdoor into people’s psyches, inviting them to reconsider other preconceived ideas that an artwork touches on.

You tend to conceive objects that imitate or recreate nature and, in works like Fish Hammer, you even suggest a sort of revenge of other species towards the human being. Why this particular interest about animal, wild life?

Western societies and philosophies are very human-centric in their narratives about the world. Humans are the protagonists and the planet is here to serve them. Even from a young age, playing outside in nature surrounded by insects, this view didn’t really reflect my experience of the world and this led me to create pieces that often start from an imagined non-human perspective.

Several of your works were created with recycled materials when you were at the Recology artistic residence. Do you think there is any other way for design to be sustainable?

The program at Recology was one of my favorite residency experiences. It was an incredible opportunity as an artist to be able to give people’s junk a new life. It was also an interesting challenge to starting from objects rather than ideas. The act of scavenging was a very sobering experience, seeing the sheer volume of perfectly good items that would get thrown away. People would come and drop off their junk, from building materials to electronics, and then you would have to retrieve it before it was crushed into the pile, never to be used again.

Design does not have to be unsustainable in nature. The unsustainability is built into our economic system, to use the cheapest materials, to get us to dispose of our devices rather than repairing and upgrading them. Environmental costs are externalized and omitted from the profit equation. Some companies will pay lip service to being more sustainable, for instance by cutting down on packaging, while retaining their most damaging practices because addressing them would hurt their bottom line.

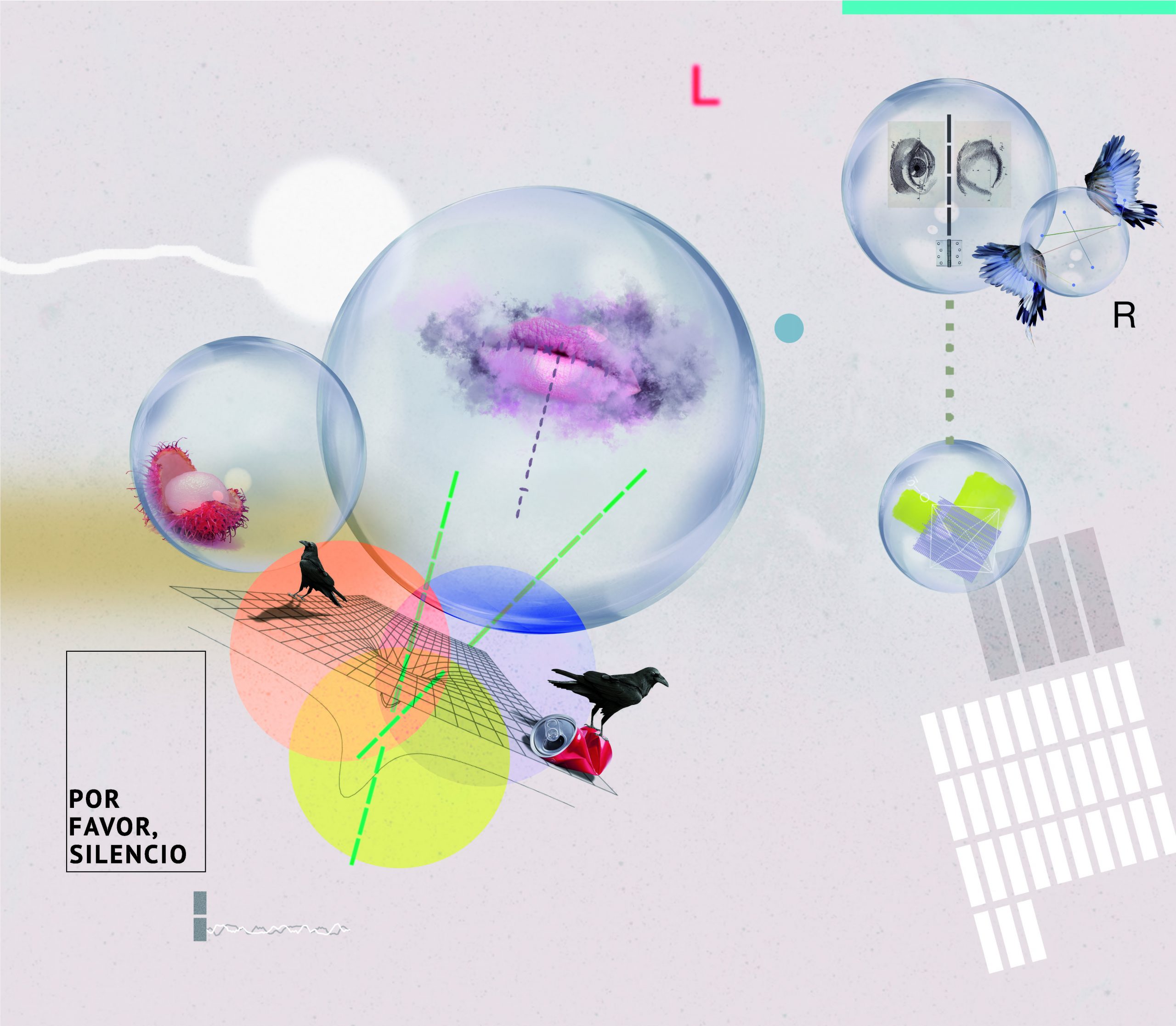

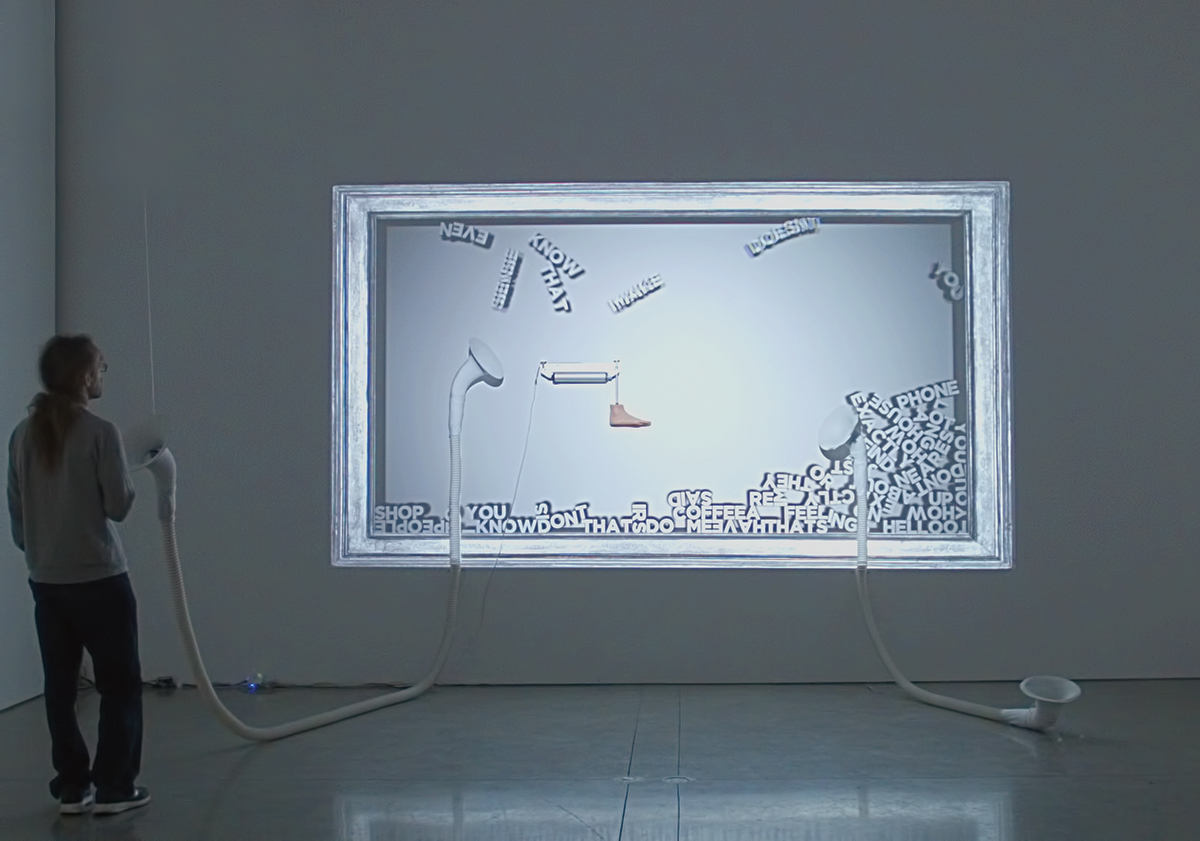

The Robotic Voice Activated Word Kicking Machine reflects on the language and words wasted in this sort of phatic communication with technologies. It is as if we do not give relevance to words or as if we take away their meaning…

Phatic communication, using sound as a means of connection with semantics taking a back seat, comes naturally to humans. Like body language, it’s most likely something we were doing before complex language existed. Being able to communicate with machines using sound is incredibly powerful. The trick that’s been played on us is to use this kind of subconscious communication with cloud devices that are outposts for corporate entities whose main interest is either selling us more stuff or selling our data about us.

In Ghost Writer, you reflect on how the tools we use to communicate affect the content and tone of what we say. How was born that work of art?

If you send a birthday card to someone, you are probably going to put more thought into the content of the message than if you were sending an SMS. As communication technologies have become faster and more efficient, our written communications have become less thoughtful and more throwaway. This effect got me thinking about the communication devices as having personalities of their own. The physicality of the typewriter nicely embodies this as well. It’s in perfect working order after more than 100 years and was never intended to be disposable.

Much has been said about the surrealist nature of many of your works, but I also perceive a certain existentialist tone. Are you interested in the European artistic avant-gardes of the early 20th century?

I think my work has more in common with the Dada movement that was a precursor to surrealism. Dada used absurdity as a reaction to the chaos and violence of the first world war. My work uses absurdity as a tool to explore the seemingly unalterable path of growing consumption that society is following at the expense of a sustainable future.

You’ve been a DJ and producer of electronic music, and it’s easy to see its influence in works like House Party or The Electric Knife Orchestra. You’ve said that music transforms our relationship with space and objects that surround it, in what sense?

Music is another tool for decontextualization, allowing people to look at objects in a fresh light. In the Electric Knife Orchestra, for example, when the piece is switched off people perceive the knives and the whole installation as dangerous. When it is playing music, safety ropes are necessary as people are suddenly very eager to stick their fingers underneath knives moving at high speed. Music is also a way to create a complex choreography for a kinetic piece that people can immediately understand.

In your provocative project titled Art 3.0, far from the usual art market, “the price is algorithmically determined and proudly displayed at all times”. Is the price of art so random and at the same time so important in the present world?

I actually created this piece a few years before the NFT boom in 2021 as a critique of the speculative nature of the art world. When artworks become commodities, the price becomes intertwined with the perception of the art. It also becomes detached from any innate properties of the art and a function of external forces. When the NFT craze hit and people were selling low effort copy/paste “art” for millions of dollars which was a perfect illustration of this phenomenon.

You tend to provide and share the code for many of your projects. Do you think it’s important for art to maintain that freedom and openness opposed to the tech market?

I think artists underestimate their power to shape the future. For example, tech companies are busy building out ideas that first appeared in 90s cyberpunk fiction, including the elements that were intended to be dystopian. A lot of our tech today is profit friendly rather than human friendly, aimed at extracting our money and attention. It’s up to creatives who aren’t bound by corporate constraints to suggest visions of the future that are inclusive, sustainable and bring us together. If these visions are compelling enough then they’ll cross over into reality. To this end, harnessing open source is invaluable, providing tools that are of a similar caliber as those used in commercial environments.